Glenoid Labrum Tests

The glenoid labrum is a fibrocartilaginous rim attached around the margin of the glenoid cavity. The labrum serves several functions. By deepening the glenoid fossa, it contributes to shoulder mechanics and prevents the humeral head from rolling out of the socket. Injury to the labrum can result from a:

The compressive force can be from a fall on out-stretched hand (FOOSH). The peel back injury occurs when the shoulder is in external rotation and the long head of the biceps pulls the labrum from the rim. Clinical signs and symptoms of a labral tear may include:

Clinical Tests

At the time of this writing, there are more than 17 clinical tests for the labrum. We will prioritize a few because of their high specificity: Anterior Slide, Crank, Kim, Biceps Load, Biceps Load II, Pain Provocation, and Dynamic Labral Shear Tests. All of these tests have a common thread of incriminating the labrum via compression or traction force. So let’s look at how that’s done.

At the time of this writing, there are more than 17 clinical tests for the labrum. We will prioritize a few because of their high specificity: Anterior Slide, Crank, Kim, Biceps Load, Biceps Load II, Pain Provocation, and Dynamic Labral Shear Tests. All of these tests have a common thread of incriminating the labrum via compression or traction force. So let’s look at how that’s done.

The Anterior Slide, also known as the Kibler test, is performed in a seated position with hand on the hip and thumb pointing posteriorly. The clinician places one hand on top of the affected shoulder to stabilize the scapula. The other hand is placed on the olecranon to apply a forward and superior force along the shaft of the humerus. The result is an anterior slide of the humeral head. A positive test is pain over front of the shoulder joint line or a click.

The Crank test takes the arm overhead to 160° with the elbow flexed to 90°. A compression force is administered down the humerus while performing a scouring motion of internal and external rotation. This scouring maneuver is used to assess the cartilage of other joints in the body, i.e. hip (Scour Test) and knee (Apley Test). The intent is to capture the labrum to identify a lesion. Pain along the joint line and/or clicking would be considered a positive test.

The Crank test takes the arm overhead to 160° with the elbow flexed to 90°. A compression force is administered down the humerus while performing a scouring motion of internal and external rotation. This scouring maneuver is used to assess the cartilage of other joints in the body, i.e. hip (Scour Test) and knee (Apley Test). The intent is to capture the labrum to identify a lesion. Pain along the joint line and/or clicking would be considered a positive test.

The Kim test applies a similar load through the humerus while the scapula is stabilized and the elbow is flexed to 90°. However, for the Kim test, the upper extremity is only elevated to ~90° in the plane of the scapula. In some versions of the Kim test, clinicians have been reported to move the humerus up and down +/- 45° while applying a downward and backward force through the humerus, i.e. range of examination is 45 to 135°. A positive test would be sudden onset of posterior shoulder pain or clicking with or without a clunk. Some clinicians take the liberty of adding the scouring maneuver to the Kim test, but that is not part of the standardized technique.

The biceps load test first appeared in the literature in 2001 and later was revised to the biceps load II test. It incriminates the labrum via the attachment of the biceps tendon. The test is performed in supine with the shoulder in 90° of abduction and 90° of elbow flexion. The clinician loads the biceps by resisting the combination of elbow flexion and supination. This position is consistent with the mechanism for a “peel back” injury. Based on data by Woods et al (2011), the biceps load and biceps load II elicits very high selectivity of the long head of the biceps to produce a traction force on the labrum.

The biceps load test first appeared in the literature in 2001 and later was revised to the biceps load II test. It incriminates the labrum via the attachment of the biceps tendon. The test is performed in supine with the shoulder in 90° of abduction and 90° of elbow flexion. The clinician loads the biceps by resisting the combination of elbow flexion and supination. This position is consistent with the mechanism for a “peel back” injury. Based on data by Woods et al (2011), the biceps load and biceps load II elicits very high selectivity of the long head of the biceps to produce a traction force on the labrum.

The difference in the biceps load II test is simply the starting position. The biceps load II starts at 120° of shoulder abduction (still 90° of elbow flexion). A positive test for both versions of the biceps load test is a reproduction of pain as the biceps pulls on the labrum. These tests are unique in that the statistics reveal them to be both good diagnostic and good screening tools.

The pain provocation test, also known as the Mimori test, implicates the biceps by taking it into a position of passive insufficiency. Thus, in supine with the upper extremity placed in a 90/90 position, a traction force is applied to the biceps by passively taking the forearm into maximal pronation and elbow extension. So the motion is the opposite of the biceps load test. The test described by Mimori et al (1999) had the arm supported in the plinth. This clinician performs the test with the arm off the plinth to increase the elongation of the biceps through increased shoulder extension. A positive interpretation is the same as the biceps load, i.e. a reproduction of pain as the biceps pulls on the labrum. Unfortunately the sensitivity is quite variable for this test. It is possible that a person’s increased flexibility may not effectively traction the biceps with just elbow extension and forearm pronation.

The pain provocation test, also known as the Mimori test, implicates the biceps by taking it into a position of passive insufficiency. Thus, in supine with the upper extremity placed in a 90/90 position, a traction force is applied to the biceps by passively taking the forearm into maximal pronation and elbow extension. So the motion is the opposite of the biceps load test. The test described by Mimori et al (1999) had the arm supported in the plinth. This clinician performs the test with the arm off the plinth to increase the elongation of the biceps through increased shoulder extension. A positive interpretation is the same as the biceps load, i.e. a reproduction of pain as the biceps pulls on the labrum. Unfortunately the sensitivity is quite variable for this test. It is possible that a person’s increased flexibility may not effectively traction the biceps with just elbow extension and forearm pronation.

The dynamic labral shear test is best performed in supine with the humerus off the plinth in 90° of abduction and full ER. The humerus should be free to move. This test can be done in the sitting position, but the scapula needs to be supported and the clinician would then need to work against gravity to move the patient’s arm. The clinician places one hand on the acromion and the other hand engulfing the olecranon of the flexed elbow. The humerus is passively abd/adducted to impart a shearing force to the labrum. A palpable click is a positive test.

The dynamic labral shear test is best performed in supine with the humerus off the plinth in 90° of abduction and full ER. The humerus should be free to move. This test can be done in the sitting position, but the scapula needs to be supported and the clinician would then need to work against gravity to move the patient’s arm. The clinician places one hand on the acromion and the other hand engulfing the olecranon of the flexed elbow. The humerus is passively abd/adducted to impart a shearing force to the labrum. A palpable click is a positive test.

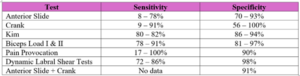

Glenohumeral Labral Test Statistics

This chart summarizes the metrics for the 7 labral tests presented. It provides the opportunity to compare the efficacy of the tests at a glance. Rarely do clinicians have time to perform seven tests for any given structure. This chart allows the clinician to strategically select the tests deemed most valuable.

Videos of all of these tests are available with the subscription to iOrtho+ Premium Web App please visit https://iortho.xyz/

- Gill HS, El Rassi G, Bahk MS, et al. Physical Examination for partial tears of the biceps tendon. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2007;35:1334-1340

- Guanche CA, Jones DC. Clinical testing for tears of the glenoid labrum. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(5):517-523

- Gulick DT. iOrtho+ Web App. DTG Enterprises LLC. 2025

- Gulick, DT. OrthoNotes, 5th FA Davis Publishing, Philadelphia. 2024

- Kim SH, Ha KI, Han KY: Biceps load test: a clinical test for superior labrum anterior & posterior lesions in shoulder with recurrent anterior dislocations, American Journal Sports Medicine. 1999;27:300-303

- Lewis CL, Sahrmann SA. Acetabular labral tears. Physical Therapy. 2006;86(1):110-121

- Liu SH, Henry MH, Nuccion SL: A prospective evaluation of a new physical examination in predicting glenoid labral tears, American Journal Sports Medicine 1996;24:721-725

- McFarland EG, Tanaka MJ, Garzon-Muvdi J, Jia X, Petersen SA. Clinical & imaging assessment for superior labrum anterior & posterior lesions. Current Sports Medicine Reports. 2009;8(5):234-239

- Mimori K, Muneta T, Nakagawa T, Shinomiya K. A new pain provocation test for superior labral tears of hte shoulder. American Journal Sports Medicine. 1999;27:137-142

- Myers TH, Zemanovic JR, Andrews JR. The resisted supination external rotation test. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;33(9): 1315-1320

- Parentis MA, Mohr KJ, ElAttrache NS. Disorders of the superior labrum: review & treatment guidelines. Clinical Orthopedics Related Research. 2002:77-87

- Stetson WB, Templin K. The crank test, the O’Brien test, & routine magnetic resonance imaging scans in the diagnosis of labral tears. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2002;30(6):806-809

- Walsworth, MK, Doukas WC, Murphy KP, Mielcarek BJ, Michener LA. Reliability & Diagnostic Accuracy of History and Physical Examination for Diagnosing Glenoid Labral Tears American Journal Sports Medicine. 2008; 36(1):162-168

- Wilk KE, Reinold MM, Dugas JR, Arrigo CA, Moser MW, Andrews JR. Current concepts in the recognition & treatment of superior labral (SLAP) lesions. Journal of Orthopedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2005;35:273-291

- Wood VJC, Sabick MB, Pfeiffer RP, Kuhlman SM, Christensen JH, Curtin MJ. Glenohumeral muscle activation during provocative tests designed to diagnose superior labrum anterior-posterior lesions. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011;39(12):2670-2678