Challenges of SI Testing: Part 1

Does the sacroiliac joint move? This have been one of the most contentious issues in sacroiliac joint (SIJ) research (Vleeming, 2012). Studies up until 1634 suggested the SIJ only moved during pregnancy. In the 17th century, the SIJ was reported to have a synovial membrane, confirming its mobility. By the mid-19th century, researchers demonstrated that most of the sacral movement occurred around a transverse axis and was named ‘nutation’ (forward nodding) and ‘counternutation’ (backward nodding). In 1864, Von Luschka described the joint as a real diarthrosis, i.e. a mobile joint with a joint cavity between two bony surfaces. In 1909, Albee used a specific staining technique to validate the synovial nature of the SIJ and confirm joint mobility.

The SI joint is stabilized by a network of ligaments and muscles. The normal sacroiliac joint has been shown to have approximately 2-4 mm of movement. So yes, the SIJ does move!

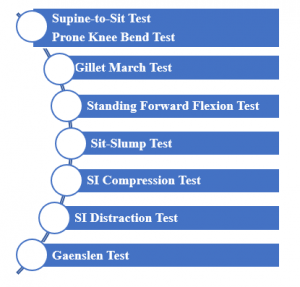

The next step is attempting to assess such a small quantity of movement. There are at least 15 tests in the literature to incriminate the SIJ. We will explore 8 in The Challenge of SI Testing – Part 1 and 6 in The Challenge of SI Testing – Part 2 (next week).

In addition to the test descriptions, the metrics, and the clustering of test results will be discussed. The 8 tests included in Part 1 are:

As the test implies, the Supine-to-Sit Test begins in supine with both lower extremities extended.  The clinician palpates the medial malleoli to assess leg length (image 1). While holding the position on the medial malleoli, the patient moves into long sitting (image 2). Leg length is re-assessed. Ideally, there should be no relative change. However, if the malleolus of the involved leg moves distal (gets longer), there may be a posterior ilium rotation. If the malleolus of the involved leg moves proximal (gets shorter), there may be an anterior ilium rotation.

The clinician palpates the medial malleoli to assess leg length (image 1). While holding the position on the medial malleoli, the patient moves into long sitting (image 2). Leg length is re-assessed. Ideally, there should be no relative change. However, if the malleolus of the involved leg moves distal (gets longer), there may be a posterior ilium rotation. If the malleolus of the involved leg moves proximal (gets shorter), there may be an anterior ilium rotation.

Prone Knee Bend Test is obviously performed in the prone positio n wi

n wi th the clinician assessing relative leg length with legs extended (left image). Both knees are passively flexed to 90° (right image) with leg length reassessed. Interruption of this test is similar to that of the supine-to-sit test. A change in leg length is considered a positive test. If one leg appears shortened in the prone knee extended position and appears to lengthen in the prone knee flexed position, this may imply a posterior innominate rotation.

th the clinician assessing relative leg length with legs extended (left image). Both knees are passively flexed to 90° (right image) with leg length reassessed. Interruption of this test is similar to that of the supine-to-sit test. A change in leg length is considered a positive test. If one leg appears shortened in the prone knee extended position and appears to lengthen in the prone knee flexed position, this may imply a posterior innominate rotation.

Gillet March Test has been described to be done using bilateral and unilateral techniqu es.

es.

Bilateral: In standing, palpate the inferior aspects of both PSISs as the hip is flexed to 120 degrees

Unilateral: In standing, palpate the inferior aspect of 1 PSIS and sacral base as the hip is flexed to 120 degrees (image). This can be repeated by palpating the other PSIS and flexing the ipsilateral hip. Flexion of the hip should result in rotation downward and medial of the ipsilateral PSIS. A positive test is one of reduced mobility of the ipsilateral PSIS suggesting a reduction of posterior rotation of that innominate.

Standing Forward Flexion Test also begins with palpating the PSIS bilaterally while the patient forward bends. Movement should be symmetrical. Asymmetrical movement implies dysfunction on the side that moves first and furthest.

Sit-Slump Test is obviously performed in sitting. The clinician palpates the bilateral sacral sulci while patient slowly moves from a position of backward bending to forward bending, i.e. erect posture to a slumping posture (image). Detecting an overall reduction in motion is difficult since there are no normalized standards. However, asymmetric movement or a reproduction of symptoms is a positive test result.

There are 2 tests identified as the decompression and distraction tests and they can be easily confused if one does not understand the physiology of the tests. The tests are both named for the anterior aspect of the iliosacral junction. Thus, the compression of the anterior aspect of the iliosacral junction is identified as the SI Compression Test. Of course, that means the posterior aspect of the iliosacral junction is being distracted (hence the co

There are 2 tests identified as the decompression and distraction tests and they can be easily confused if one does not understand the physiology of the tests. The tests are both named for the anterior aspect of the iliosacral junction. Thus, the compression of the anterior aspect of the iliosacral junction is identified as the SI Compression Test. Of course, that means the posterior aspect of the iliosacral junction is being distracted (hence the co nfusion). The SI Compression Test (left) can be performed in sidelying or supine. A force is applied through the lateral aspect of the iliac crest(s). A positive test is a reproduction of SI joint pain. The SI Distraction Test distracts the anterior aspect of the anterior iliosacral junction and compresses the posterior aspect. This test is performed in supine (right). The clinician applies a lateral force to the ASIS’s through the palms of the hands. A positive test is reproduction of SI joint pain.

nfusion). The SI Compression Test (left) can be performed in sidelying or supine. A force is applied through the lateral aspect of the iliac crest(s). A positive test is a reproduction of SI joint pain. The SI Distraction Test distracts the anterior aspect of the anterior iliosacral junction and compresses the posterior aspect. This test is performed in supine (right). The clinician applies a lateral force to the ASIS’s through the palms of the hands. A positive test is reproduction of SI joint pain.

Gaenslen Test is a maneuver in which 1 knee is brought to the chest while the other leg remains extended. At end range, overpressure is added. Thus, imparting torsion to the SIJ. Additional stress may be applied to the SIJ if the extended leg is placed over the edge of the table. Again, a positive test is the reproduction of symptoms in the region of the SIJ.

Gaenslen Test is a maneuver in which 1 knee is brought to the chest while the other leg remains extended. At end range, overpressure is added. Thus, imparting torsion to the SIJ. Additional stress may be applied to the SIJ if the extended leg is placed over the edge of the table. Again, a positive test is the reproduction of symptoms in the region of the SIJ.

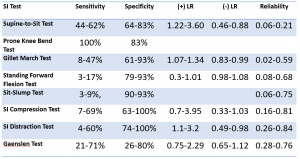

All of the tests discussed are assessing SI mobility via sagittal plane motion or by imparting varying magnitudes of force. The table below summarizes the metrics of these tests. Despite having limited motion, some of the tests have relatively strong diagnostic properties.

Levangie (1999) reported individual test sensitivities were low (8%-44%), as were negative predictive values (28%-38%), for identifying the presence of innominate torsion in the Gillet, standing forward flexion, sitting forward flexion, and supine-to-sit tests. With the exception of the Gillet test (odds ratio = 4.57), combining tests did not improve performance characteristics.

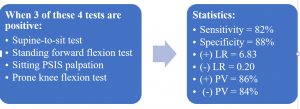

On the other hand, sometimes clustering of clinical tests can significantly increase the statistical value. A good example of this is the combination supine-to-sit, standing forward flexion, sitting PSIS palpation, and prone knee bend tests. When 3 of 4 tests are positive, the statistics are notably better:

Stay tuned for additional SIJ tests in the next BLOG post: The Challenge of SI Testing – Part 2

For more cutting edge orthopedic information or iOrtho+ Premium Mobile App, please visit the learning modules at https://iortho.xyz/

- Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard J. Evaluation of clinical tests used in classification procedures in pregnancy-related pelvic joint pain. European Spine Journal. 2000;9(2):161-166

- Arab AM, Abdollahi I, Joghataei MT, et al. Inter- and intra-examiner reliability of single & composites of selected motion palpation & pain provocation tests of the sacroiliac joint. Manual Therapy. 2009;14:213-221

- Bemis T, Daniel M: Validation of the long sitting test on subjects with iliosacral dysfunction, Journal of Orthopedics & Sports Physical Therapy 1987;8:336-345

- Blower P, Griffin A. Clinical sacroiliac tests in ankylosing spondylitis & other causes of low back pain. Annales of Rheumatic Disorders. 1984;43:192-195

- Broadhurst N, Bond M. Pain provocation tests for the assessment of sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Journal Spinal Disorders 1998;11:341-345

- Cibulka MT, Koldehoff R: Clinical usefulness of a cluster of sacroiliac joint tests in patients with and without low back pain, Journal Orthopedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 1999;29:83-92

- Dreyfuss P, Michaelsen M, Pauza K, McLarty J, Bogduk N. The value of medical history & physical examination in diagnosing sacroiliac joint pain. Spine. 1996;21(22):2594-2602

- Flynn T, Fritz J, Whitman J, et al. A clinical prediction rule for classifying patients with low back pain who demonstrated short-term improvement with spinal manipulation. Spine. 2002;27:2835-2843

- Freburger JK, Riddle DL: Measurement of sacroiliac joint dysfunction: A multicenter intertester reliability study, Physical Therapy 1999;79:1135-1141

- Gulick DT. iOrtho+ Mobile App. DTG Enterprises LLC. 2020

- Gulick, DT. OrthoNotes, 4th FA Davis Publishing, Philadelphia. 2018

- Ham SJ, Walsum DP, Vierhout PAM. Predictive value of the hip flexion test for fractures of the pelvis. Injury. 1996;27:543-544

- Kokmeyer D, van der Wuff P, Aufdemkampe G, Fickenscher T. Reliability of multi-test regimens with sacroiliac pain provocation tests. Journal Manipulative Physiological Therapeutics. 2002;25:42-48

- Laslett M, April C, McDonald B, Young S. Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: validity of individual provocation tests & composites of tests. Manual Therapy. 2005;10:207-218

- Laslett M, Williams M. The reliability of selected pain provocation tests for sacroiliac joint pathology. Spine. 1994;19:1243-1249

- Levangie PK. Four clinical test of sacroiliac joint dysfunction; the association of test results with innominate torsion among patients with & without low back pain. Physical Therapy. 1999;79(11):1043-1057

- Levangie PK. The association between static pelvic asymmetry & low back pain. Spine. 1999;24(12):1234-1242

- Meijne W, van Neerbos K, Aufdemkampe G, van der Wurff P: Intraexaminer and interexaminer reliability of the Gillet test, Journal Manipulative Physiological Therapeutics 1999;22:4-9

- Ozgocmen S, Bozgeyik Z, Kalcik M, Yildirim A. The value of sacroiliac pain provocation test in early active sacroiliitis. Clinical Rheumatology. 2008;10:1275-1282

- Palmer MC, Epler M: Clinical Assessment Procedures in Physical Therapy, Philadelphia, 1990, J.B. Lippincott

- Potter N, Rothstein J. Intertester reliability for selected clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint. Physical Therapy. 1985;65:1671-1675

- Riddle D, Freburger J. Evaluation of the presence of sacroiliac joint dysfunction using a combination of tests: a multicenter intertester reliability study. Physical Therapy. 2002;82:772-781

- Robinson HS, Brox JI, Robinson R, et al. The reliability of selected motion & pain provocation tests for the sacroiliac joint. Manual Therapy. 2007;12:72-79

- Russell A, Maksymovich W, LeClerq S. Clinical examination of the sacroiliac joints. Arthritis Rheumatism. 1981;24:1575-1577

- Soleimanifar M, Noureddin K, Arab AM. Association between composites of selected motion palpation and pain provocation tests for sacroiliac joint disorders. Journal of Bodyworks and Movement Therapies. 2017;21:240-245

- Tong HC, Heyman OG, Lado DA, Isser MM. Interexaminer reliability of three methods of combining test results to determine side of sacral restriction, sacral base position, & innominate bone position. Journal of American Osteopathic Association. 2006;106:464-468

- Toussaint R, Gawlik C, Rehder U, Ruther W. Sacroiliac dysfunction in construction workers. Journal Manipulative Physiological Therapeutics. 1999;22:134-138

- Toussaint R, Gawlik CS, Rehder U, Ruther W. Sacroiliac joint diagnostics in the Hamburg Construction Workers Study. Journal of Manipulative Physiological Therapeutics. 1999;22:139-143

- van der Wurff P, Hagmeijer RH, Meijne W: Clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint-a systematic methodological review. Part 1-reliability, Manual Therapy 2000;5:30-36

- Vincent-Smith B, Gibbons P: Inter-examiner & intra-examiner reliability of the standing flexion test, Manual Therapy 1999;4(2):87-93

- Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Masi AT, Carreiro JE, Danneels L, Willard FH. The sacroiliac joint: an overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications. Journal of Anatomy. 2012;221(6):537-567

- Walsh J, Flatley M, Johnston N, Bennett K. Slump test: sensory responses in asymptomatic subjects. Journal Manual Manipulative Therapy 2007; 15(4): 231-238

- Woerman AL: Evaluation & treatment of dysfunction in the lumbar-pelvic-hip complex. In Donatelli R, Wooden MJ (eds): Orthopedic Physical Therapy, Edinburgh, 1989, Churchill Livingston