To Measure or Not To Measure: Hip Structural Assessment

Structural tests of the hip can include screening for fractures or local lesions and assessing leg length discrepancy. Fracture screening and the identification of local lesions may be a red flag, whereas a leg length discrepancy can be assessed in different ways and may not involve any intervention at all.

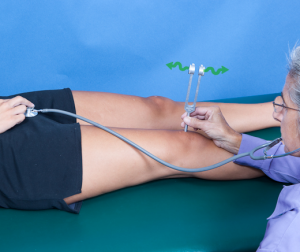

Patella-Pubic Percussion Test

The Patella-Pubic Percussion test is used to assess for hip fractures or structural pathology. The test involves placing the stethoscope on the pubic bone. Out of respect for a patient’s privacy, handing the bell of the stethoscope to the patient and allowing him/her to place the stethoscope on the pubic bone could avoid an awkward situation. With the stethoscope in your ears, vibrate a tuning fork and place it on the patella. You are listening for a disruption in the conduction of the sound. Disruption may occur if there is some type of lesion (tumor) or a fracture. Comparing the involved to uninvolved side will be necessary to have an appreciation for subtle changes in the quality of the sound transmission. The statistics for this test are very unique. Both the sensitivity (94-96%) and specificity (86-96%) are excellent. Positive likelihood ratio (6.73-21.6) is also huge, while the negative likelihood ratio (0.14-0.7) is low. Thus, this test is an exceptional test for both screening and diagnostic purposes to pick up a structural pathology.

Hip Fulcrum Test

The Hip Fulcrum test is used to identify femoral shaft stress fractures. Sitting on the edge of a plinth or a chair that is high enough to have his/her feet off the floor, the clinician weaves a hand underneath the suspected injured region of the femur to the contralateral thigh. Body weight through the ischial tuberosity provides proximal stabilization. The clinician applies a vertical force at the distal femur to create a fulcrum of the femur. This test is excellent for ruling out femoral stress fractures (sensitivity = 93%) and moderate for diagnostic purposes (specificity = 75%).

Sign of the Buttock

Sign of the Buttock

The Sign of the Buttock is a unique test used to identify a number of non-musculoskeletal pathologies. This test looks to a combination of findings to identify serious pathology. With the patient in supine, the clinician passively performs a straight leg raise (SLR) and notes the degree of hip flexion before limitation or onset of symptoms occurs (left figure). The knee is then flexed and additional hip flexion is attempted (right figure). Under normal circumstances, one would expect hip flexion to increase when the knee is flexed. If this does not happen, one should question the origin of the buttock pain. Is it a local lesion or is it referred from the hip, sciatic nerve, or hamstrings?

If any of the following seven signs/symptoms are present, this would be considered a “red flag” and an appropriate referral should be considered.

- Buttock large and swollen and tender to touch

- Straight Leg Raise limited and painful

- Limited trunk flexion

- Hip flexion with knee flexion limited and painful

- Empty end feel on hip flexion

- Non capsular pattern of restriction at hip (flexion, abduction, IR)

- Resisted hip movements painful and weak, especially hip extension

Although this test has been reported in several manuscripts and textbooks, there isn’t any statistical data published. An example of how this test is used was described by VanWye (2009) with a 77 year old male with a diagnosis of lumbosacral and hip osteoarthritis. The patient was referred to physical therapy. When the clinician identified a positive “sign of the buttock,” empty end feels for all hip motions, and severe night pain, a referral was made. With the assistance of additional testing, a diagnosis of primary lung adenocarcinoma with widespread metastases (including the hip) was made. This is an excellent example of the use of a clinical test to identify a “red flag.”

Measurement of Leg length

Leg length assessment is something that classically performed as part of a low back or lower extremity examination. A limb length difference is not unusual. As many as a third of the population may have a 1 cm or less. One study reported 32% of military recruits had a 1/5- to 3/5-inch difference between the lengths of their legs. Patients who have differences of 3.5 – 4% of total leg length (about 4 cm or 1-2/3 inches in an average adult) may limp or have other gait abnormalities. These differences may also require the patient to exert more effort to walk.

The measures used to assess leg length do not tell us whether the discrepancy is a structural (anatomic) or a functional (apparent) difference. Nonetheless, they are non-invasive and simple to do. In supine, the clinician applies a bilateral traction force to the lower extremities to equilibrate the pelvis. Option #1 is a measurement made from the prominence of the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the distal medial malleolus of the ipsilateral leg. While option #2 is a measurement made from the prominence of ASIS to the distal lateral malleolus of the ipsilateral leg. Why would one chose option #1 vs option #2? The primary reason is a significant anomaly of one leg, i.e. quad atrophy, knee swelling, etc. Crossing over from the ASIS to the medial malleolus can result in abnormal measures if the quadriceps are atrophied or the knee is edematous. Thus, using option #2 should be considered.

To ascertain if the leg length discrepancy is due to femur versus tibial length, the Galeazzi assessment (AKA Allis Sign and Skyline Test) can be performed. This is simply a visual inspection of alignment. In supine, passively flex the patient’s hips and knees to approximately 45° and 90° degrees, respectfully. Place medial malleoli together. If the knees are not level in height, the tibial length may be asymmetrical (image on left). If the tibial tuberosities are not even, the femur length may be asymmetrical (image on right).

To ascertain if the leg length discrepancy is due to femur versus tibial length, the Galeazzi assessment (AKA Allis Sign and Skyline Test) can be performed. This is simply a visual inspection of alignment. In supine, passively flex the patient’s hips and knees to approximately 45° and 90° degrees, respectfully. Place medial malleoli together. If the knees are not level in height, the tibial length may be asymmetrical (image on left). If the tibial tuberosities are not even, the femur length may be asymmetrical (image on right).

Once leg length is determined, it is the purview of the clinician to determine if it is significant and/or if it should be corrected. For more cutting edge orthopedic information in iOrtho+ Premium Mobile App, please visit https://iortho.xyz/

- Adams SL, Yarnold PR, Clinical use of patellar-pubic percussion sign in hip trauma. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 1997;12:173-175

- Bache JB, Cross AB. The Barford Test – A useful diagnostic sign in fracture of the femoral neck. The Practitioner. 1984;228:305-307

- Bolz S, Davies GJ: Leg length differences and correlation with total leg strength, J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1984;6:123-129

- Clarke GR: Unequal leg length: An accurate method of detection and some clinical results, Rheumatol Phys Med 1972;11:385-390

- Fisk JW, Balgent ML: Clinical and radiological assessment of leg length, N Z Med J. 1975; 81:477-480

- Gulick DT. iOrtho+ Mobile App. DTG Enterprises LLC. 2020

- Gulick, DT. OrthoNotes, 4th FA Davis Publishing, Philadelphia. 2018

- Johnson AW, Weiss CB, Wheeler DL: Stress fractures of the femoral shaft in athletes-more common than expected: A new clinical test, Am J Sports Med 1994;22:248-256

- Kazemi M. Tuning fork test utilization in detection of fractures: a review of the literature. Journal of Canadian Chiropractic Assoc. 1999;43(2); 120-124

- Magee D. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company; 2008.

- Misurya RK, Khare A, Mallick A, Sural A, Vishwakarma GK. Use of tuning fork in diagnostic auscultation of fractures. Injury. 1987;18:63-64

- Nye NS, Covey CJ, Sheldon L, Webber B, Pawlak M, Boden B, Beutler A. Improving diagnostic accuracy and efficiency of suspected bone stress injuries: Algorithm and clinical prediction rule. Sports Health. 2016;May-June;8(3):278-283

- Reider B: The orthopedic physical examination, Philadelphia, 1999, W.B. Saunders.

- Reiman MP, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests of the hip: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J of Sports Medicine. 2013;47:893-902

- Sawyer JR, Kapoor M. The limping child: a systematic approach to diagnoses. American Family Physician. 2009;79(3):219

- Tiru M, Goh SH, Low BY. Use of percussion as a screening tool in the diagnosis of occult hip fractures. Singapore Medical Journal. 2002;43:467-469

- VanWye WR. Patient screening by a physical therapist for nonmusculoskeletal hip pain. Physical Therapy. 2009;89(3):248-256

- Woerman AL, Binder-Macleod SA: Leg-length discrepancy assessment: Accuracy and precision in five clinical methods of evaluation, J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1984; 5:230-239

- Woerman AL: Evaluation and treatment of dysfunction in the lumbar-pelvic-hip complex. In Donatelli R, and Wooden MJ (eds): Orthopedic physical therapy, Edinburgh, 1989, Churchill Livingstone.