Testing Cervical Spine Stability

Testing Cervical Spine Stability

In a previous post, “When are C-Spine Radiographs Needed?” we discussed the importance of fracture screening for the cervical spine (April 3, 2024). This is an essential step prior to performing any cervical spine clinical tests. Then, assessing cervical spine stability must be determined prior to embarking on any manual techniques and/or therapeutic exercises. Screening for instability or hypermobility of the cervical spine can be valuable in determining the appropriate course of treatment. If instability is identified, imaging may be required prior to initiating treatment. Let’s explore 5 commonly recognized clinical tests to assess ligamentous integrity and cervical spine stability.

Alar Ligament Test is performed in supine or sitting. The clinician palpates the spinous process of C2 and then sidebends the cervical spine slightly to each side. Testing is recommended in 3 positions (neutral, flexion, extension) to account for variations in the orientation of the alar ligament. The test is positive when there is a delay in the movement of the C2 spinous process in the opposite direction of the sidebending motion. This reveals laxity, i.e. sidebending right tests the left alar ligament.

Alar Ligament Test is performed in supine or sitting. The clinician palpates the spinous process of C2 and then sidebends the cervical spine slightly to each side. Testing is recommended in 3 positions (neutral, flexion, extension) to account for variations in the orientation of the alar ligament. The test is positive when there is a delay in the movement of the C2 spinous process in the opposite direction of the sidebending motion. This reveals laxity, i.e. sidebending right tests the left alar ligament.

Transverse Ligament Test, AKA the Cranial Atlas Lift Test, is performed in supine with the head cradled in the clinician hands. The clinician placed his/her fingers over the atlas and lifts the client’s occiput/C1 to translate head and C1 anterior on C2. Care should be taken not to flex or extend the neck. The position should be held for 15 seconds. A positive test for atlanto-axial instability is vertigo, nystagmus, paresthesia, or soft endfeel.

Transverse Ligament Test, AKA the Cranial Atlas Lift Test, is performed in supine with the head cradled in the clinician hands. The clinician placed his/her fingers over the atlas and lifts the client’s occiput/C1 to translate head and C1 anterior on C2. Care should be taken not to flex or extend the neck. The position should be held for 15 seconds. A positive test for atlanto-axial instability is vertigo, nystagmus, paresthesia, or soft endfeel.

Sharp-Purser Test is used to assess for atlas-axis instability. The test is performed in sitting with the head slightly flexed on the neck. The clinician stabilizes the spinous process of C2 with one hand and places the other hand on the client’s forehead. A posteriorly-directed force is applied through the forehead contact. A positive test is when the head slides posteriorly or the endfeel is soft. This indicates a reduction of subluxed atlas on axis.

Sharp-Purser Test is used to assess for atlas-axis instability. The test is performed in sitting with the head slightly flexed on the neck. The clinician stabilizes the spinous process of C2 with one hand and places the other hand on the client’s forehead. A posteriorly-directed force is applied through the forehead contact. A positive test is when the head slides posteriorly or the endfeel is soft. This indicates a reduction of subluxed atlas on axis.

If the Sharp-Purser test is negative, the Aspinall Test can be performed to assess the integrity of transverse ligament. The clinician stabilizes the flexed occiput on the atlas as an anteriorly-directed force is applied to the atlas. A positive test is a soft endfeel or if the client reports symptoms including esophageal pressure and/or other neurologically-related cord compression symptoms.

If the Sharp-Purser test is negative, the Aspinall Test can be performed to assess the integrity of transverse ligament. The clinician stabilizes the flexed occiput on the atlas as an anteriorly-directed force is applied to the atlas. A positive test is a soft endfeel or if the client reports symptoms including esophageal pressure and/or other neurologically-related cord compression symptoms.

Lateral Shear Test assesses the presence of segmental instability. When in supine, the clinician’s 2nd MCP of 1 hand contacts the transverse process of C1. The MCP of other hand contacts the transverse process of C2. A gentle force is provided in equal & opposite directions through each hand contact. A positive test is increased translation between C1 & C2. Please note, if the clinician’s hands are not in the same plane, the shear force will produce unwanted rotation.

Lateral Shear Test assesses the presence of segmental instability. When in supine, the clinician’s 2nd MCP of 1 hand contacts the transverse process of C1. The MCP of other hand contacts the transverse process of C2. A gentle force is provided in equal & opposite directions through each hand contact. A positive test is increased translation between C1 & C2. Please note, if the clinician’s hands are not in the same plane, the shear force will produce unwanted rotation.

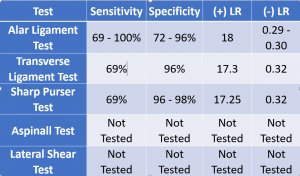

The statistical values for each of these tests are displayed below. As one can see, 2 of the tests (Aspinall and Lateral Shear) do not have any metrics reported in the literature. This makes it difficult to know if the test has any clinical merit. How much credence should a clinician give the test results? Without this information, one might wonder if s/he should be the tests at all. The other 3 tests have respectable specificity and a high (+) likelihood ratio, i.e. they are strong diagnostic tools. These data are important in placing value on the tests.

Should one of the first 3 tests be positive, additional imaging may be in order prior to embarking on any treatment techniques. For videos of these techniques and more cutting-edge orthopedic information download iOrtho+ Premium Web App. Subscribe for the low annual rate of only $9.99. If you prefer to just try iOrtho+ Premium for 1 month, you can do so for only $1.99 Please visit https://iortho.xyz/ Prior blog posts are also available at https://iortho.xyz/

- Aspinall W. Clinical testing for the craniovertebral hypermobility syndrome. Journal of Orthopedics & Sports Physical Therapy 1990;12:47-54.

- Dobbs A. Manual therapy assessment of cervical instability. Orthopedic Physical Therapy Clinics of North America. 2001; 12:431-454

- Gulick DT. iOrtho+ Mobile App. DTG Enterprises LLC. 2024

- Gulick, DT. OrthoNotes, 5th FA Davis Publishing, Philadelphia. 2023

- Meadows JJ, Magee DJ: An overview of dizziness and vertigo for the orthopedic manual therapist. In Boyling JD, Palastanga N (eds): Grieve Modern Manual Therapy: the vertebral column, 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone, 1994

- Olson KA, Paris SV, Spohr C, Gorniak G: Radiographic assessment & reliability study of the craniovertebral sidebending test, Journal Manual Manipulative Therapy 1998;6:87-96

- Osmotherly PG, Rivett D, Rowe LJ. Toward understanding normal craniocervical rotation occurring during the rotation stress test of the alar ligament. Physical Therapy. 2013;93(7):986-992

- Pettman E: Stress tests of the craniovertebral joints. In Boyling JD, Palastanga N (eds): Grieve Modern Manual Therapy: the vertebral column, 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone, 1994

- Uitvlugt G, Indenbaum S: Clinical assessment of atlantoaxial instability using the Sharp-Purser test, Arthroscopy Rheumatology 1988;31(7):918-922